THAI CHARMS AND AMULETS

Journal of the Siam Society Vol. 52.2d (1964)

by Phya Anuman Rajadhon พระยาอนุมานราชธน (Acting President, Royal lnstitute )

Tbe belief in and use of charms and amulets as magical

protection against dangers and misfortunes, and also to bring love, luck and power is a world-wide one.It is not confined to primitive races only, but also to be found among modern peoples of every nation and faith. In fact “the thought and practice of civilized peoples can not be cut off as with a knife from the underlying customs and beliefs which have played a determining part in shaping the resulting products, however much subsequent knowledge and ethical evaluation may have modified and transformed the earlier notions”. 1 For this reason, every faith and religion has in one form or another certain cults and formulas, as inherited from the dim past and handed down from generation to generation, from the old belief of magic and superstition, which are paradoxically contrary to the real teaching of the religion’s founder. This is inevitable; for the mass of humanity that forms the woof and warp of the woven fabric of faith of the great religions, is composed of many levels of culture.

A.B.Griswold says in his “Doctrines and Reminders of Theravada Buddhism” that

“within the Theravada there are two very different sorts of Buddhist-rationalists and pious believers.”2 This may be applied equally to other religions: there are always implicitly two sorts of believers within the same religion, the intellectuals and the pious people.

___________________________________________________________

1 Preface to the Comparative Religion by E.O. James, 1961. 2 The Arts of Thailand, p. 28, 1960 A.D,

____________________________________________________________

It is with the latter that one can find abundant phenomena of charms and amulets in belief and practice.

In the Thai language charms and amulets are called collectively

khawng-khlang ( “ของขลัง“) which means “sacred, potent objects or talismans.”

Traditionally, this is divided and classified into four major classes, namely:

I Khruang-ran.g (เครื่องราง), II Phra Khruan.g (พระเครื่อง),

III Khruan.g pluk-sek (เครื่องปลุกุเสก) and IV Wan ya (ว่านยา ) 1

I Khruang-ran.g . This is a material substance transformed from

its natural and normal state mostly into stone or copper. Such a

thing is supposed to he imbued inherently with magical power. If

held in the mouth or carried or worn on the body of a person, it will

provide him or her with invulnerability and protection against

dangers or misfortunes. ” Guns will not fire, sharp things will not wound if fired at or struck at the wearer” (ยิงไม่ออกพั่นไม่เข้า) who has such a magical object with him or her. The khruang-rang is sub-divided roughly into two sub-classes,

namely:

( a) Khot (คด ) • A certain kind of talismanic stone found

in certain animals, birds, fishes, crabs and trees; (for instance teak

and bamboo). Included also in this sub-class are certain stones

found in termite hills, stone eggs, certain kinds of ores and lek-lai (เหล็กไหล)2 and a certain kind of stone called “khot akat” ( คดอากาศ), literally the “khot of the sky.” Probably it is a meteoric stone or fragment. There are many kinds of “khots “, more than enumerated here, and no text books relating to the subject as far as I know are in printed form. Some khots I have seen resembled in material substance black stone or oxidised copper. Whether, perhaps they were artificial, I am unable to verify.3

(b) Unclassified. Included in this sub-class are certain seeds found in jack fruit, tamarind, krathin thet ( กระถินเทศ– agacia faraesiana ), pradu ( ประดู่ – pterocarpus indicus ), saba ( สะบ้า – entada phaseoloides ), satü ( สะืืตืือ– caudia chrysantha) and makha (มะค่า-lntsia bejuga ).4

______________________________________________________________________

1 The transcription of Thai words is based mainly on the Transcription of Thai

Characters into Roman, The Royal Institute, Bangkok, 1954.

2 A miraculous iron characterized by its quality to become soft if held over candle-fire.

3 Probably the “khot” and the Burmese amade are one and the same thing. See

Shway Yoe, The Burman, his life and notions, 3rd ed. 1909. p. 46.

4 Latin words from McFarland, Thai-English Dictionary·

______________________________________________________________________

With the exception of the jack-fruit tree, all the above trees and vines are “leguminosae” in species, and are found more or less as indigenous growths in Southern Thailand, the northern part of the Malay Peninsula. Any seed or pod from the aforesaid species of trees if found unusually in its natural state to be copper, it is deemed a miraculous object which commands awe and trust, and can be utilized for its supposed inherent vital force as khrüang – rang.

Parenthetically, there is a well-known belief among the older

generation that if a man is born, as a freak of nature, with a lone

copper testis, he will have in himself a certain magical property.

Such a prodigy cannot be slain by any means with ordinary

weapons but by impalement only. There have been once or twice,

if my memory serves me right, mentioned in old chronicles of such

a notable man. Ondoubtedly, the belief in the magical efficacy

of copper is an echo of the Copper Age preserved superstitiously

by man that any such object, a novel and a freak of nature, is a

thing of awe and wonder.

Sometimes, I am told, for lack of such rare magical things

as enumerated above, people will resort to artificial ones by

fashioning them in copper as representations of the aforesaid

natural ones. Khrüang-rang both sub-class (a) and (b) may be

set, mounted or encased with precious metals and strung to a gold

chain to be worn as a necklace. Sometimes they are enmeshed

with fine wires strung to a piece of thread to be hung around

the neck, or wrapped with a narrow piece of white cloth, then

rolled and twisted to be worn as a charm or an amulet. If a natural

one is sizable, in particular the “khot” stone, it may be broken

in smaller pieces for convenience of wearing.

Included too in sub-class (b) are adamantine cat’s-eye ( เพชรตาแมว) and rat’s-eye ( เพชรตาหนู), solid boar’s tusk, canine tooth of tiger or “sang” 1) ( สาง), boar’s or elephant’s tusk broken and lodged in a tree. The latter elephant tusk has a special name in Thai kamchat kamchay ( กำจัดกำจาย= to expel and disperse).

Also included in this sub-class (b) are buffalo’s and bull’s horns

which flash with a radiant light in darkness as if in flames. Any

object of this class, (or part of it if it is a big one) may be ornamented

with precious metal and worn or carried by the owner

as a protection against any danger.

_________________________________________________________

1. Sang is an old tiger which can transform it self into a man, or vice-versa a

magician who can turn himself into a tiger. It is a were-tiger in Thai folklore.

__________________________________________________________

The names of these talismanic objects of the Khrüang-rang

are mentioned frequently in Thai historical romances, particularly

in the well-known story of “Khun Chang Khun Phaen” ( ขุนช้างขุนแผน ) . Without an elementary knowledge of the objects of Khrüang-rang, one will not be able to have a clear idea of popular beliefs and lore of the good old days among members of certain

social groups in Thailand. One studies such survivals of the

present day in order to know something of the past and to understand

the present. To ignore such studies for various reasons is

to understand incorrectly the growth and development of the

thoughts and ideas of the folk.

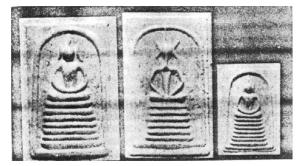

II Phra-Khrüang (พระเครื่อง). Allied to objects in class I

or Khrüang-rang are certain classes of figurines representing

attitudes and episodes of the life of the Lord Buddha. In fact,

the Thai word Phra Khrüang is a shortened form of Phra

Khrüang-rang (Phra = the lord + khrüang-rang).

These figurines are of three sizes, large, medium and small

which can be utilized as a necklace pendant or carried conveniently

by a person. One or many of these figurines may be worn or carried at the same time after the manner of folk thinking that the bigger the number, the better the safeguared against dangers.

(The more the water, the fewer fish will die; the less the water, the more fish will die” is a Thai saying.)

These sacred figurines are divided into four classes according to materials used and

the process of making them. They are:

(a) Terracotta figures. These are made of fine clay, or a

mixture of clay, pollens from certain kinds of flowers and “wanya”

(see Class IV). The ingredients of the mixture vary in different

degrees in different “schools of teachers” and the formulas are

a jealously kept secret.

(b) Votive tablets of Phra Phim ( พระพิมพ์) meaning Buddha

figurines cast in a mould.

The materials used are of many kinds.

They may be made purely of clay or chalk powder after a certain

magical pronouncement and religious process of a mixture of

certain metals such as iron, copper, tin, lead or certain alloys of

metals. Sometimes gold and silver and mercury are added also.

These again are varied according to the ideas of different “school

of teachers”.

Votive tablets were originally made in tens of thousands

and deposited in caves or enclosed in a stupa or Phra Chedi

(= pagoda) for the pious purpose of reminding the people of their

reverential feeling for the Lord Buddha and his religion; at the

end of five thousand years after his death he will be succeeded

by another Buddha named Sri Arya Metrai ( ศรีอารยเมตรัย) or

Phra Sri Arn ( พระศรีอารย์) in colloquial Thai. Undoubtedly this

belief was influenced more or less by Mahayan, or the Northern

School of Buddhism in contrast to Hinayan, the Southern School

of Buddhism, which has been adopted as the national religion

of Thailand. Historically, there are traces of Mahayan Buddhism

embedded in literature, folklore and ancient monuments in

Thailand which formed the belief of the mass of people or popular

Buddhism in Thailand and the neighbouring countries.

In the process of time more and more such votive tablets

were deposited in stupas as erected, sometimes made not in fullfilment

of a vow but to be used rather as talismans. Old ones have

been discovered from time to time in old or ruined phra chedi,

and many of them fetch high prices determined by the types

and localties where they were discovered. Evidently there are fake

ones too and a knowledge of how to distinguish the real from

the faked ones becomes an art in itself.

(c) Cast figurines. The Casting of these Buddha figurines

has a ritual process in the same manner as casting Buddha images,

but there are certain details that differ, of course, with different

“school of teachers”. The metal cast is either iron, nak ( นาก –

an alloy of gold and copper, the red gold), or silver.

(d) Carved figurines. Materials used for carving are the

wood of certain kinds of trees, such as the sacred fig tree, sandalwood

tree, teak tree and star gooseberry tree. The latter is called

in Thai mayom ( มะยม ) . The second syllable in the word “yom”

has the same identical sound as two other Thai words niyom ( นิยม )

and Phra Yom ( พระยม ). The former means “liked, approved,

respected” (Sanskrit-niyama), and the latter means the Hindu

God of the Underworld (Sanskrit-Yama) feared by all evil spirits.

This is no doubt a play on words which have the same sound

but different meaning, carried far back to the superstition that

the same sound will produce the same effect in the realm of magic.

Apart from such specific woods, the figurines of Buddha may

be carved also out of stone, “khot” (see above), ivory, or tiger’s

canine tooth.

III Khrüang pluk-sek. Before dealing with objects pertaining

to this class, which are numerous, it is necessary to say something

first on the word pluk-sek, for it enters magically not only

this class of talismanic objects, but also other kindred ones as

well. Pluk-sek in Thai means “to arouse the potency of a person or an object by the use of a spell or incantation”; hence “a consecration, a blessedness” in a sense. A spell in the Thai language is khatha-akhom ( คาถาอคม) or wet-mon (เวทมนตร์). These two sets of words are used synonymously by the people, even by the

adepts of magical arts. In fact the four words khatha, akhom,

wet and mon have Sanskrit and Pali words as their origin. They

are gatha, agama, veda and mantra.

Gatha is a verse of a song in Sanskrit and Pali, but khatha

in Thai, apart from its original sense, means also a spell.

Agama in one sense means the Vedas while in Thai akhom

means a spell to be used magically when inscribing or tattooing

certain cabalistic letters, arithmetical figures, circles, squares,

etc. (Yantra) on an object or on the physical body of a person.

Vedas, the sacred scriptures of the Hindus, is Wet in Thai,

which means spell or a set form of words supposed to have magical

power.

Mantra is in Thai pronunciation mon and both mean spell

also. The two terms Veda and mantra, though synonymous in

the Thai language, have different uses. The Vedas mean spell

in relation to post- Vedic Brahminism and the mantras mean

mostly spells in connection with Popular Buddhism. The Thai

knew the first four books of the Vedas, i.e. the Samhitas or the

collection of mantras only, and called them Phra 1 Wet(พระ เวท) .

1. Phra ( พระ ) is vara in Sanskrit and Pali. It is an honorific word in Thai meaning

“lord, precious, etc., to be found in such Thai words, Phra Chao = God,

Phra Jesu = Lord Jesus, and Phra Mahamad = Prophet Mohamad. Phra

alone means also God, a Buddhist monk, or a king or a hero in Thai romance.

If a recitation of certain selected verses from the Buddhist scriptures

is applied with a purpose as a protection against danger or for

the promotion of health and wealth, it is called mon (mantra)

and if otherwise it is called wet (Veda). Hence the confusion of

meanings of these four words with the tendency to merge into

one another in popular usage.There is another type of wet-mon or spell peculiar perhaps

to the Thai where purely Thai words are recited, or sometimes with Pali terms interspersed here and there for sacredness. Many of the Pali words therein are corrupted ones, while some of the

Thai words are sometimes unutterable or unprintable in everyday

speech because of their obscenities in meanings. Paradoxically,

such a spell is to be pronounced in a loud voice during incantation

in order to have an instant effect on a person or thing concerned.

This type of spell is called Mon Maha Ongkan

( มนตร์มหาโองการ = the mantra of the Great Aumkar or Aum) or in

brevity and in Thai pronunciation mon or Ongkan for the reason

that most of the spells begin with the Hindu mystic sound Aum .

Many Thais of older generation, particularly the uncultured ones,

know more or less of these mantras or spells. They have them

by heart for emergency use, but will not divulge the secret for fear

of indecency or want of kind consideration,1 ) but they may be

told to someone as humorous anecdotes during informal conversation

among intimates.

Sometimes the set form of words to be recited or muttered

is a long one, a selection of initial letters of certain words of the

spell being used as a sort of cabalistic word in place of the full length

text. It is deemed that such an abbreviated form will have

the same magical effect not unlike that of the magic “abracadabra”.

This abbreviated word is called in Thai “the core of the heart” (หัวใจ); probably the same as the words hridya and bija in Sanskrit which mean heart and seed.

I may add here also, as a parenthesis, that when inscribing

or tattooing the word-form in its abbreviation, Cambodian letters

are used for sacredness; only numeral figures are written, in Thai.

Why ? In the old days all sacred Buddhist scriptures were inscribed

on palm leaves with the khom or Cambodian characters unlike

the present day when they have all been replaced by the Thai

alphabet. It has been a traditionai belief and preserved unreflectively

among the folk that khom or Cambodian letters of the old

days were not unlike runic characters with regard to magical

purpose.

Now we can dicuss at some length those objects that pertain

to class III, Pluk-sek. Any artificial objects, apart from Buddha

figurines in class II, have to pass through certain processes of

“pluk-sek” in Order to arouse in them their magical property

by the use of certain magical formal figures such as magic squares,

circles or other and certain incantations appiopriate to the objects

or purposes concerned. Talismanic objects in class I Khrüangrang

and also even Buddha figurines in class II Phra Khrüang, if

they are deemed to grow effete in their magical functioning,

may go through the same process of “pluk-sek” in order to re-enforce

and renew their potency. What has been said here applies

equally to objects in class IV Wan-ya also.

As there are a large variety of objects pertaining to the class

of “pluk-sek,” only certain ones which are comparatively well known,

or so far as I know, will be described as the following.

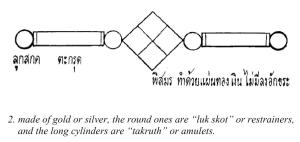

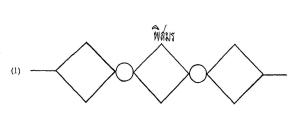

Takrut ( ตะกรุด ) or amulet (in its limited sense). This class

of objects is a long hollow cylinder in shape with varying length

and thickness. Usually, as far as is known, it is about two inches

long more or less; the shortest one is about half an inch, while

its thickness varies as to material used, ranging from about half

an inch in circumference to about an eighth of an inch. What

has been described here is an approximation only, for there is

to my knowledge no hard and fast rule relating to a standard

measurement. The material used is a small sheet of metal, such

as gold, nak (red gold), silver, copper, tin or lead, cut to the desired

size and inscribed on a small piece of paper or on the metal itself

with mystic letters or other forms and figures as determined in

a particular formula of pluk-sek which differs with each “school of teachers”.

The sheet of metal is then rolled to form a long

hollow cylinder. Sometimes a small twig of bamboo is cut to

the desired length and enlarged with ample hollowness for convenience

of stringing. The takrut is worn with a gold or silver

chain, or with a cotton string, consecrated or otherwise, as a necklace,

a chain worn over the right shoulder as one wearing a sash,

an armlet or a girdle, for protection against dangers or for other

magical purposes as determined by each particular treatise. Usually

the takrut as worn is not a single object but comprises many pieces,

all of the same uniform sizes and lengths as a set or otherwise.

Sometimes magic figures to be inscribed on the takrut are

elaborated into many figures and lines of letters so as to form a

complete set. These cannot be inscribed in totality on a single

small piece of metal but have to be spread out on a number of

takruts; hence the wearing of a number of “takruts” of uniform

size in a single chain. They are usually 3, 5 or 7 in number and such

takruts are called takrut phuak ( ตะกรุดพวก) or associated takruts.

Sometime takruts of various sizes and lengths are worn on a single

chain, because these takruts belong to different “acharns” ( อาจารย์ –

acharya) or teachers of different schools of magic which have

each a peculiar virtue of sacred potency, and one ought not to

miss wearing them if one has a chance of owning them. There

are also Ornaments made in the shape of a takrut which have

nothing to do with magic, but are for adornment only.

Salika. This is a very tiny kind of takrut. The word salika

is a Pali word ( Sanskrit – sarika ) which means a mynah bird which

features often in folk-tales as a sweet talker. Hence the name

of this kind of takrut. Whoever has a salika takrut inserted in a

narrow space between his or her teeth, will find himself or herself,

while talking to someone to have sweet and melodious speech

commanding goodwill towards him or her. Hence a common

saying “he is a salika lin thong i.e. a golden-tongued salika”.

If it is found convenient to insert the salika in the space

between the teeth, the salika may be made in a tiny thin form

instead of rolling it into the takrut shape. Sometimes the salika is inserted on the inner lower lid of either eye to command goodwill from other people toward oneself when in sight. Some authorities

say that in this case, it is a misnomer to call it salika. Its

appropriate name is takrut prasom net ( ตะกรุดประสมเมตร) which

means literally in my own rendering “Takrut of meeting with

the-eyes”, i.e. the takrut which has the power to condition the

meeting of friend or lover to be united in wedding or for gaining

wealth, luck or fortune as desired.

Phismon ( พิสมร ). A talismanic object made from a piece

of leaf of talapot palm inscribed with mystic figures and letters

through a magical process, and woven into a square shape about

an inch in diameter. It is strung on a silk thread, for reason of

its relative strength, rather than on an ordinary cotton thread.

It is worn crosswise from the left shoulder.1

Phismon was used during one of the Thai traditional New

Years, of which there are two – Trut Thai ( ตรุษไทย ) and Trut

Songkran – the water-throwing festival.2 The former, Trut

Thai, falls on the last day of the 4th lunar month (March-April).

In the old days it was a time for people to make merit by offering

food to monks and to wear a phismon during the end of the Old

Year as a protection against evil spirits still lurking as supposed

during and after a ceremonial expulsion at the end of the Old

Year. There was during those days an official ceremony, participated

in by both Buddhist priests and brahmins of the royal

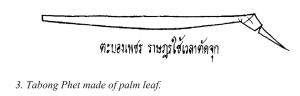

court, when palm-leaf “phismon and tabong phet (ตะบองเพชร)” 3

phismon

1. The description of “phismon” is based on a description and a rough sketch

kindly supplied to me some 20 years ago by my friend the late Phra Devabhinimit,

one of the famous Thai artist painters.

2. See J.S.S. Vol. 42 (July, 1954) pp. 23-30

3. Tabong phet means baton made of diamond. In realty it is made of a piece of

palm leaf, and is now still used in the “tonsure ceremony” as a survival of

the old days. See a sketch of tabong phet in plate II No. II of G.E. Gerini,

Chulakantamangala or the Tonsure Ceremony, Bangkok, 1895 A.D.

were distributed to the people who longed for some

tangible protection against evil spirits and the bad luck of the

Old Year.1) The Trut Thai is still observed feebly by the older

generation up to the present day when food is presented to priests

and monks as a special occasion only.

There are also phismons made either of gold or silver which

have no magical value, but are for ornamental purposes only,

unless they have passed through a magical process. They are

worn over the left shoulder in a cross-wise direction strung to a

gold chain, or over both shoulders across the breast and fastened

in front with a pin or a brooch. When many are worn on a chain,

there are also takruts in between the phismons, and again there

are gold beads at both ends of the phismons and takrut called

in Thai luk skot ( ลูกสะกด ) which act as “restrainers” ( สะกด )

or separators. The word “phismon” is curious. It seems to be a word in

a Sanskritized form. It is written as bismara but pronounced

phismon in Thai, but no word bismara is, to my knowledge, to

be found either is Sanskrit or Pali, the classical languages of

the Thai. There is a word basmala in Malay, Arabic in origin,

which is a formula for the words “In the name of Allah, the Merciful, the

Compassionate”. It is inscribed on a piece of paper and enclosed

in a small metal case and hung by a string and worn as a necklace.

I describe this from memory only when I saw half a century ago

a Pathan wearing such a thing around his neck. He told me

that it is called bismala. It is possible that the Thai phismon and

bismala or basmala may come from the same source.3)

There are two other words in Malay which are similar to

Thai words in connection with magic. They are the words kaphan (กะพ้น ) and khun (คุณ ). The former is usually juxtaposed to another Thai word to form a synonymous couplet peculiar to the Thai language as Yukhong Kaphan ( อยู่คงกะพ้น ).

______________________________________________________________________________

1. See H.M. King Chulalongkorn, The Royal Monthly Ceremonies of the Year

( พระราชพิธิ่สิบสองเดือน) in Thai.

2. See article “Basmala” in Encyclopaedia of Ethics and Religion

Yukhong is no doubt an indigenous Thai word meaning invulnerability;

the same meaning attaches also to the word “kaphan” – a word

of doubtful origin. The Malay has a word kabal with a similar

sound and meaning i.e. invulnerability. Khun in Thai means

an incantation by which a piece of raw hide is magically reduced

greatly in size to harm an enemy sending it with means to enter

the victim’s body. The magical raw hide will resume gradually

its normal size inside the victim, and he will suffer great pain

and die in agony. If I remember right Malay has a word “guna”

with a similar meaning. There is no doubt that because of similar

conditions of mind among the simple folk of the people of South-

East Asia, there have been in the past mutual borrowings of

magical practice. This may apply to other peoples as well; for

“civilization is only skin-deep” . One will find similar practices

and ideas, though modified and transformed to modern ideas,

among people of every race or nation.

Pha prachiat (ผ้าประเจียด). This is a piece of cloth about

the size of a handkerchief or a napkin inscribed with yantra. In

the days when people usually wore a singlet or otherwise with a

pha khama ( ผ้าขาวม้า )loincloth i.e. a scarf hung loosely on a shoulder or as a sash as one’s upper garments, the pha prachiat was worn

as a neck-or an arm-band when going out as a proof against

weapons, as a protection from malignant spirits and to avert any

mishaps. Later, when one wore a coat, a hat or cap, the pha

prachiat was kept either in the coat-pocket or in the hat or cap.

There are a number of books in Thai, mostly in manuscripts

in private possession, which treat the subject of yantras more

or less systematically with copious patterns and designs of the

yantras. No one who is a stranger to this mystical art will be

able to make yantras effectively from book knowledge only. He

must also know the mysteries communicated or imparted ritually by a teacher. Hence yantras made by a priest famed for his holiness are eagerly soughr for. Psychologically, any object magical in its origin must acquire a religious significance ritually before it

can be regarded as an object of khrüang pluk-sek.

The ritual process by which a yantra can be produced effectively

is roughly as follows:

After the usually preliminary purificatory act as required

in all solemn rites, the practitioner will begin by making an address

invoking the help, firstly, of the holy Triple Gems, i.e. the

Buddha, his Law and his Council of Orders; next come the chief

deities of Hinduism and semi-divine beings, including in their

train also certain rishis or holy seers who are traditional preceptors

peculiar to the particular rite on hand; then come one’s parents

and teachers, both in the past and present as relevant to one’s

particular profession. In certain rites evil spirits, both local

and foreign, are coaxed and coerced at the same time.

The list of such conglomerations of beings varies more or

less in different “school of teachers”, and some of the names

in the iist, particulary the rishis or seers, are compted and difficult

to identify with Indian ones. Some of them bear local names only.

The invoking address is not confined to the production of yantras,

but carried out also as a preliminary act traditional for other

solemn undertakings, for instance, the rite relating to the casting

of Buddha images, the writing of certain literary compositions

and the annual homage to teachers and instructors by students.

The tradition is a beautiful one as an expression of gratitude to

one’s benefactors, both imaginary or real and in the past and

present, and to ask solemnly for grace, goodwill and success in

any undertaking or learning. The tradition has a great influence

upon the attitude of most of the Thai towards their parents,

teachers and mentors.

After the afore-said act, the practitioner will concentrate

his mind religiously and begin to draw the yantra. He has to hold

his breath hile mumbling certain specific gathas, or, in other

words, a magic spell, and at the same time he must not withdraw

certain specific lines. What has been described here is an imperfect

statement of a layman who has never been instructed in

the mysteries as imparted by a teacher of the art.

Akin to pha prachiat there are a number of specific yantras

inscribed on a piece of cloth or Paper. They are not known by

name as a class like pha prachiat but called individually by the

names they bear with the word yantra as a prefix. Their uses in

magic are the same as pha prachiat, save that they are not worn

or carried by a person but hung somewhere as a means of protection

against unseen danger from the phi or evil spirits. Two of

these yantras, well-known ones, are described herewith.

Yan Thao Wessuwan ( ยันต์ท้าเวสสุวรรณ). It is a yantra

a figure image of King Wessuwan who is a yakhsa or supernatural

being of gigantic size. He is no other than Kuvera or Vaisravana

the Hindu king or chief of the evil spirits, a sort of Pluto, and

also a god of wealth and a regent of the North. His vehicle, unlike

that of other Hindu chief deities, is man. In Thailand there has

been a belief among the folk that Wessuwan is the guardian of

new-born babies which are liable to be taken or killed very easily

by numerous evil spirits that swarm and lurk somewhere near

the vicinity where a child is bom. Hence a Yantra bearing his image

is hung over a baby cradle or cot. Evil spirits seeing Wessuwan’s

image in the yantra will be frightened and give it a wide-berth

for Wessuwan has a terrible and ugly appearance as a giant holding

always a very massive bludgeon. In Hindu mythology he has

three legs as his means of locomotion. Why is he very interested

in human babies? Because they are his human vehicles. In the

old days, some fifty years ago, there were printed copies of this

yantra on sale in the market. I do not know whether these printed

yantra were merely ordinary printed ones or whether they have

passed through a proper magical process. Anyhow, to the folk

this is not important so long as they had faith in tbe efficacy of

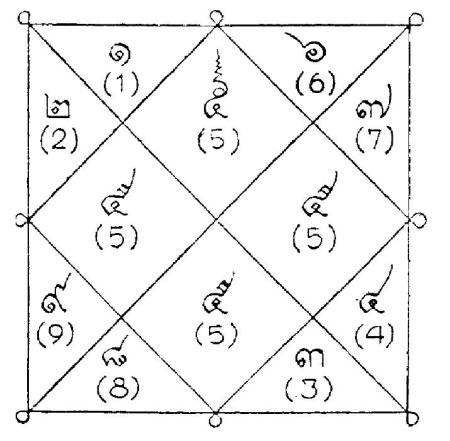

the yantra.Yan Trinisinghe ( ยันต์ตรีนิสิงเห ). A yantra in the form of

a square with four equal sides, and a smaller one interposed

diagonaily. A line is drawn across either angle of the two squares;

thus forming four little squares diagonally within the main one.

There are also three small circles to each side at the outer rim of

the main square, two at each corner and one in the middle between

the two. Thus within the main square there are four little squares

and two half-squares each at every corner. In these eight spaces

certain numeral figures are inscribed, so that when added up in

a straight line they will give certain mystic numbers. Here is the diagram of the yantra:

Note figure 5 at the top with a spiral crest. It is a sacred

and mystic symbol known as unalom in Pali and urna in Sanskrit.

It is a traditional curled tuft of hair between the eye-brows peculiar

to the Lord Buddha.

The Yan Trinisinghe has many functions in connection

with white magic. In former days when a baby was born, a number

of these yantras were hung by a string around the perimeter of

the room where the mother with her baby was lying near a fire

after giving birth. This is a safe-guard against danger from evil

spirits especially the phi krasü ( ผีกระสือ). 1

There are many kinds of yantras of the type of yan trinisinghe.

No doubt they are elaborations of the said yantra even

though they bear different names and functions.

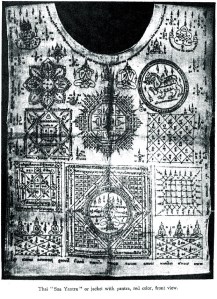

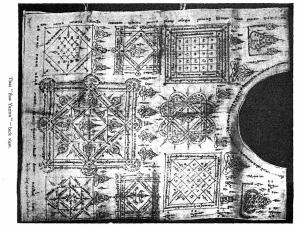

Süa Yan ( เสื้อยันต์). Akin to pha prachia is the “süa yan”

or a jacket inscribed with yantra. It has the same use and function

as a magical protection not unlike the pha prachiat. In principle

the süa yan jacket and the pha prachiat are evidently one and

the same thing. The difference lies in that the former has ample

space for drawing yantra in details, enabling one to include on

the jacket many patterns of yantra to comparatively satisfy one’s

needs as desired, while the latter cannot.

The süa yantra jacket is usually red and the inscription black.

Those that I have seen which belonged to the King’s wardrobe

were each in one of the seven colours corresponding to the seven

days of the week, (each of which has a specific colour relating

to the apparel one wears).2) These royal jackets are called in

Thai court language chalong phra ong long raja ( ฉลองพระองค์ลงราชะ )

which means literally “royal jacket inscribed with raja”,

(which in this instance means yantra), identical in sound and

meaning to the Malay word raja.

___________________________________________

1 See “The Phi’’ J.S.S. Vol. 41, pt. 2. 1954.

___________________________________________

Tattooing. Five decades ago or more most male Thai particulary

among the folk, tattooed themselves for invulnerability.

Travel in the old days outside one’s own village was an adventure,

with danger both from human beings and the phi or evil spirits.

One had to be a law to oneself in some outlying places. Hence

to have certain potent magical tattooed charms always on oneself

as a safeguard was better than none. Tattooing was also done

by other classes of people too, sporadically, for the healing of

certain diseases magically. The practice of tattooing for such

purposes survives weakly up to the present day.

In Northern Thailand tattooing was practised to the extent

that both thighs, down nearly to the knee and up to the waist

were totally tattooed. Seen from a distance, if scantily clad,

the tattooed man appeared to wear black short trousers. Tattooing

of yantra may be done on any part of a human body – arms,

hands, chest, back and even on the crown of the head, and

sometimes on the nape and chin. Prominent tattooed marks

are usually made on the breast and back, for the reason that

here are comparatively wider spaces for one to include certain

yantras which require more room for inscribing.1)

Evidently the tattooing of oneself with yantras and the

inscribing of them on a süa yan jacket seem to be one and the

same in principle; the difference lies in that the former is made

on a human living skin but the latter on a cloth. There is an apparent

advantage of the former over the latter in that to have a

charm always permanently with one is better than to wear one

with a süa yan jacket. One need not worry about losing such a

valuable thing. On the other hand, the wearing of a jacket of

süa yan has a compensating advantage over the former for one

will not suffer obvious pain at the initial stage during tattooing.

On this assumption I am inclined to believe that the süa yan jacket

might have been a development from tattoaing yantris.

Tattooing with a yantra has a rite of its own. It is to be

done traditionally within the sanctuary of a “bote” (Buddhist

chapel). After having made a customary obeisance before the

Buddha image, the tattooing begins under the supervision of an adept,

a priest or a layman, who will recite in a subdued voice

certain incantations throughout the time while the puncturing

of skin is in progress. When the tattooing is completed, the

tattooed man will have to face a more painful ordeal of pluk-sek

which is specific and different from what has been described. The

tattooer will strike hard with his open hand on the tattooed yantra

many times, until the designs of the yantra tattooed emerge distinctly

and prominently on the skin. There may be a test done

on the tattooed man by throwing something hard at him, or striking

him with a sharp instrument and if he comes out unscathed, it

means that the ritual process is magically a success. I am here

describing what I got from an informant, and I am unable to

verify the fact, for very few people I have come across can enlighten

me much with any authority. It seems to be in one respect something

of an initiation ceremony into manhood for young men.

There are no books on tattooing magically I have ever come

across, though there may have been many patterns and designs

kept by professional tattooers which were meant more for decoration

than for magical purposes. I am inclined to believe that

they use the same kind of yantra as selected from such books

on yantras. Perhaps there may have been some specific patterns

that are used exclusively by tattooers. In my younger days, some

sixty or more years ago, I saw certain tattooing designs appearing

on certain persons’ thighs often which I have never come across

in books on yantras. Perhaps it is too late now to find such

specimens. I may add here that a person with a tattooed yantra

or one who can say by heart certain spells will superstitiously

not eat carambola fruit or bottle gourd for fear that the charm

and spell he has with him will deteriorate in potency.

There were, also, two tattooed designs of by – gone days,

one of which I can remember vividly but hesitate to describe them,

for they border on vulgarity. However for academic purposes

I will write here roughly what they are. These two tattooed designs

are no other than phallic symbols representing both male and

female generative organs. They are known representively as ai

khik ( อ้ายขิก) and ee pü ( อีเป๋อ). No one can enlighten me what they mean either literally or etymologically; save that the prefixing words “ai” and “ee” are appellations for male and female used now in a derogatory sense. I was able to draw one of them

sketchily when I was a boy through a vagary of youth.

These two patterns of dual phallic symbols were usually

tattooed, either one or the other, on a thigh or on a forearm above

the wrist. The “ai khik” was the more frequent, for it could be

drawn easily in a grotesque shape with a tail and two legs added

in a rearing position. 1 I have never come across either of them

nowadays. Strange to say, as told to me, a person with a tattooed

ee pü has to express in sacrilegious words or acts things going

against his own Buddhist religion, if he wants the charm to operate

effectively.

The ai khik was also made, as a detachable object of a little

size, of metal (usually copper or silver) or of certain kinds of

wood. It is similar in shape to the Hindu linga. Many pieces of

these little things were worn on a string round a male child’s waist;

while a female one would wear instead a chaping (จะปิ้ง) – an

ornamental gold or silver genital shield suspended from a string round a small girl’s

waist. It is a Malay word of Portuguese origin chapin which

means a metal disc to cover the hole of anything.

Many ai khik objects were worn around a small boy’s waist,

but sometimes they were worn alternately on the same string with

other miniature metal padlocks, bells, and objects in the shape

of a chilli or red pepper pod. Such a string of magical objects

may have survived up to the present day, probably in outlying

places far from urban influence. I am told that they are, when

worn, a proof against weapons far those that are tattooed with

such figures, and as a protection from animal’s teeth and fang

which is in the Thai idiom “fangs and tusks” ( เขี้ยวงา). I believe

the practice of wearing these little things and also the chaping

the little girl wears to hide her nudity was to avert the evil eye,

which idea seems to be forgotten now among the Thai word durai ( ดูร้าย ) in ancient Thai law books meaning literally “ evil look”. Probably it may mean “evil eye” or “drishtadosha” in Sanskrit.

In certain localities in out – of – way places, one will still sometimes

come across phallic symbols of a comparatively large size

in the shape of the Hindu linga. They are mostly made of wood,

crudely done and lying or hanging on small tree branches around

or in front of a spirit shrine. One will know at once that a female

spirit has her abode there: Such thing is called in Thai dokmai

chao (ดอกไม้เจ้า) or “flowers of chief phi“ as an offering to her.

I saw some years ago while passing along a “klong” ( canal ) in a

boat, actuaily in Bangkok, a spirit shrine with many such “chao’s

flowers” hanging there. Many farangs (Westerners) also have

seen them and have asked me as to the reason why. It is a relic

of “the good old days” revived as a practical joke by a certain

old gentleman now long dead on the sophisticated folk who

look at things materially and realistically.

Luk-om (ลูกอม). Anything of a globular shape is called

“luk” in Thai and “om” means to hold in a mouth. The

“luk-om” is, in this instance, a ball which one can hold in the

mouth – a name for a certain class of khrüang pluk-sek. The

materials used as ingredients to form into a ball of luk – om are

many. It can be made of a composition of stone, lime, wax,

silver, etc. The best and well – known one is a luk-om of solidified

mercury or quick-silver. Here is the secret formula.

File down a silver baht coin into powder of ¼ baht in weight.

Mix the silver powder with pure quick – silver of one baht in weight.

(To have pure quick-silver, mix it with one ladleful of boiled rice.)

The mixing is done in a small mortar, stirring well with a pestle

until they adhere to each other sufficiently to become a compact

little ball. Put it in a piece of cloth and tie it into a compress

with a piece of string attached for hanging. Hang it above the

mouth of a boiling pot for a day; the quick-silver will thicken

into a solid. Take a kaffir lime ( มะกรูด – Citrus Hystrix, McFarland’s

Siamese-English Dictionary) and cut its top open. Insert the

quick-silver into the lime and close it with the piece of the lime which has been cut as a lid, pinning it with a silver of wood. Boil the lime with the quick-silver in it until the quick-silver becomes a solid mass in a ball about the size of a thumb, very weighty

and having a glossy surface. The quick-silver now has a magical

property. Anybody having with him such quick-silver will be

free from misfortunes and accidents. If it is put in his mouth

he will feel no thirst. It goes so far in popular belief that whoever

holds it in mouth will feel rejuvenated. Though old, his skin

will become smooth, his wrinkles and the folds of skin will

disappear. He will in the end be able to fly and become a phethyathon

(semi-divine being, the vidyadhara of Hinduism). Having

a magic solid quicksilver with you, when going into a jungle, evil

spirits will not dare to harm you. A friend of mine jokingly said

he once lived in a jungle for some time and was not molested by

evil spirits because he had with him such magical quicksilver. But

when he left the jungle, after a few days he had an attack of

high malaria fever. Assuredly the making of quicksilver into a

solid mass which gives a magical property of the alchemist’s art.

This solid quick-silver may be compared to the “Philosopher’s

mercury” of Mediaeval Europe.

Included in this class III khrüang pluk-sek, are the phirot

arm and finger ring ( แหวนพิรอต ),1) used by officiates in traditional

ceremonies, the nang kwak ( นางกว้ด = “she who beckons”)

made of metal,2 mit maw ( ÁÕ´ËÁÍ – “a master knife” inscribed

with gathas, a weapon against the phi ) and many others too

numerous to enumerate and describe herein.

As already described, the khrüang pluk-sek are consecrated

objects aroused into their magical potency by the use of certain

incantations and other ritual acts. Many of these incantations

are excerpts from certain gathas or stanzas from Buddhist literature,

and these are certain mystic abbreviations of the texts. A

well-known one is the formula Namo Buddhaya shortened into

_________________________________________________________

1. See “phirot ring” in Gerini’s Chula-Kantamangala, p.154. Also in “Bracelets

de sorciers au pays Thai” (Institute Indochinois pour l’ Etude de 1’ Homme,

1941, torne iv).

2. See “Nang kwak” in Clasz IV Wun- Ya.

__________________________________________________________

five initial letters of the five syllables na, ma, bha, dha, ya and

interpreted as the five names of the Buddhas of the period of

the age of the world (the kalpa in Sanskrit and Pali). E.O. James

in his Comparative Religion (p. 40) says rightly that “before anything

can be venerated as an object of worship it must acquire a

religious significance, that is to say, condition religious behaviour”

and in another place he says “The Indian does not interpret life

in terms of religion, but religion in terms of life” (p. 43). Look

with a generous mind on the world’s great religions and one will

not wonder why magic and superstition still form an integral part

of the faith in every religion in its popular aspect, for it takes all

sorts and conditions of humanity to form a world.

Parenthetically, there appear in a book of yantra ( คําภีร์พุทธรตนมหาย้นต์) a set of 14 stanzas of gatha, or “spell” in this instance, which are meant to be inscribed specifically

each on 14 different yantras. The first and the fourteenth

stanzas in Pali are as follows:

“Pajotā dhamma bhāhotu jotavaro satāvoha tāva riyo

suvatabhā dharo yogo chasusmmā” (first stanza).

“Ti loka magga hana komataṃ nayo sabba dayo mahasamapa

dhamsa yi ti loka maggā hana ko mataṃ nayo” (fourteenth stanza) .

It says in the book that these fourteen gathas originated

in Lankadvipa (Ceylon) during the reign of King Devanampiyadis

of Ceylon. The scholars and seers of the realm, who wished that

prosperity might reign with the great king, selected all the best

referring to the graces of the Lord Buddha and composed them

into 14 stanzas together with procedures as to their uses. These

were presented to the king who committed them to memory

and practice. By the grace and efficacy of the Fourteen Stanzas,

king Devanampiyadis had a long and prosperous reign in Anuratburi

(Anuradhapura), Lanka.

There was a great elder or maha thera named Phra Maha

Vijaya Mangala Thera, famed for his holiness, who visited Ceylon

to pay homage to the famed tooth relic of the Lord Buddha.Wishing that the great King Brahma Trailok of Jambhudvipa might derive great benefit from these Fourteen Stanzas, he copied and brought them as a present to the said king. By virtue of the

Fourteen Stanzas the great monarch became famous for his regal

splendor far and wide and foreign kings never dared to oppose

his majestic greatness and paid homage to the great king.

Whoever, whether he be a king, a samana (monk), a brahmin,

a wealthy man, or a householder, wishes to derive benefit and

happiness in the three worlds (heaven, earth and nether world)

from the Fourteen Stanzas, he has to study and commit them

to memory and to practise them daily and he will be prosperous

with happiness and good fortune until the end of his days.

IV. Wan Ya ( ว่านยา). “Wan” is the Thai name of certain

plants, mostly with tuber roots, popularly considered as a class;

and “ya” means medicine, either as a healing agent or as a poison.

The “wan ya”, as its name implies, is used mainly in folk medicine,

and many of the plants are used also in magic. Medicine and

magic among the untutored folk are inseparable in practice in

most of the remedies. Certain mantras, i.e. charms and spells,

form a preliminary and essential part for beginners in the study

and practice of the traditional art of folk medicine. Certain diseases

of unknown cause were deemed as implications of the phis or evil

spirits which lurked invisibly nearby. Without the aid of magic

one could not be sure of the efficacy of a remedy. It however,

served a useful purpose for some ailments as faith-healing does.

As most of the so-called wan ya are to be found growing

wild in jungles, it is no wonder that the lore of utilizing them as

remedial agents and posion may have come by experience originally

from jungle folk who use them as their sole medicinal remedy.

The same plant of the wan ya may have different names in different

localities, and the same name may be known in certain areas

referring to a different kind of plant. Hence it is difficult sometimes

to be Sure of the identity of any of the plants. George B.

McFarland in his Thai-English Dictionary gives under the word

“wan” some ten well-known names of the wan plants with identifyword “wan” itself. There are more than a hundred names of

wan with descriptions of the plants and their use transmitted

orally as lore which await systematic study before it is too late.

We call medicinal materials derived from plants in their crude herbal

form smun phrai ( สมุนไพร) . The word smun is still etymologically

and literally in meaning unknown, while the word phrai means

a forest or jungle from a Mon-Khmer word. Tacitly such medicinal

materials were originally forest products.

As the wan ya forms a major part of the study of folk

medicine it is outside the scope of this article. We, therefore, will

confine the discussion here to one kind of wan ya, as an example,

that has some bearing on charms and amulets.

Wan nang kwak ( ว่านนางกว้ก ). As hinted previously, nang

kwak means “she who beckons” with her hand; this wan is well known

among shop-keepers. It is used exclusively as a mysterious

magical agent to attract more buyers of the goods in the shop if

placed somewhere nearby. Here is a rough description of the

plant from memory. It is a small plant similar to the arum family

with a reddish or greenish colour. It is usually cultivated in an

earthen pot. My description here differs radically from the one

described in a certain Thai treatise on the wan plants.1

The wan nang kwak as known by botanists is Eucharis sp.2

There are one or two stalls in the week-end bazaar in Bangkok (Phramane Ground) that deal in wan plants. Perhaps there are some of the nang kwak variety in the collection. The difficuly lies in that one has to believe what the seller asserts, with no way to verify.

It is a well-known belief, mostly among women of the shopkeeper class, that whoever has the wan nang kwak in the stall will enjoy a brisk market for goods through the mysterious attraction of the wan nang kwak i.e. “she who beckons”. It may be made from the said wan either from its tuber root, certain kinds of wood of the fig family, or cast from metal, into a small figure in the image of a young woman with traditional hair style and

dress attire in an attitude of sitting side-ways on the floor, the

left hand either placed on the thigh or supported on the floor

while the right hand is raised and stretched a little forward in a

beckoning attitude of Thai style with palm downward. To beckon

with palm upward may create a misunderstanding and a sensitive

feeling to certain Thais, for it is deemed undecorous in Thai

manners.

hello dear, I am Stanley Amaechi from the Republic of Guinea bissau West Africa. Please I want to make charm for money luck and protection. here is my phone number +xxxxxxxxxxx my email address is xxxxxxxx Thanks I hope to read from you as soon as possible

What’s up it’s me, I am also visiting this site

daily, this site is actually pleasant and the people are genuinely

sharing pleasant thoughts.

You share interesting things here. I think that your blog can go viral easily, but you must give it initial boost and i know how to do it, just type in google –

mundillo traffic increase

Oh my goodness! Amazing article dude! Many thanks, However

I am experiencing troubles with your RSS. I don’t know the reason why I can’t subscribe to

it. Is there anyone else having the same RSS problems?

Anybody who knows the answer can you kindly respond? Thanks!!

Your mode of describing all in this piece of writing is truly good, all

be capable of effortlessly know it, Thanks a lot.

I’ve read some good stuff here. Definitely worth bookmarking for revisiting. I surprise how much effort you put to make such a wonderful informative website.